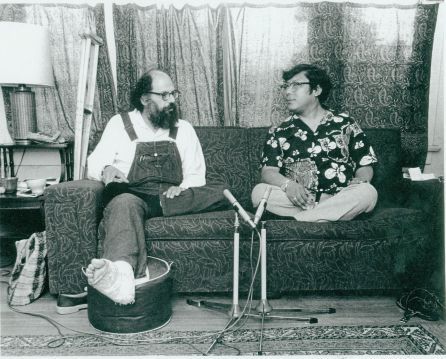

By Travis Newbill

Jane Carpenter and Sue Hammond West will lead Creative Wisdom: Maitri and Art, November 15-17

Jane Carpenter

The idea that artistry begins when the brush hits the canvass and ends when the palette is set down is questionable. An alternative view suggests that eating a pear may be as artistic of an activity as painting a still life. And, in this view, meditation practice is linked to both.

Sue Hammond West

In the upcoming program Creative Wisdom: Maitri and Art Naropa University professors Jane Carpenter and Sue Hammond West will present teachings and practices related to artistic discipline as well as meditation practice in order to guide participants in a process of exploring the ways in which we can be more awake as we create art and how we may live our entire lives in a more artistic way.

In their words:

“This weekend program explores the state before you lay your hand on your brush or your canvas – very basic, peaceful and relaxed. Here art refers to all the activities of our life, including any artistic discipline that we practice, referring to our whole being. This way of working with art is noticing the state before you make art. The potential of artistic creation is to directly point to what is true, the richness and limitless potential of the present moment of experience – nowness. We awaken our appreciation for the richness of this colorful and challenging world. Fear drops away as we engage with direct experience.”

Recently, SMC caught up with Carpenter and West and asked them to elaborate a bit on some of these pithy notions.

Shambhala Mountain Center: To begin with, how does meditation relate to art, and vice versa?

Jane Carpenter: The mind is always giving rise to ideas and thoughts. So there is always material, even on the cushion. When we’re engaged in an artistic discipline, we’re allowing the energetic patterns in that material to be used. So, I actually see a similarity of the mind being a blank canvass, and what arises in it actually being the paint and the color, or the flowers, or whatever it is.

And how about the idea of “artistic process as life?”

JC: I think it’s the ground of presence that is the thread through experiencing one’s life in an artistic way and the joy that one experiences in artistic discipline.

Sue Hammond West: You have to be authentic, and present to that authenticity, in everything that you do–in every part of your life. Then, when you go into the studio to create the art, your mind is clear. You’re not divided in your attention. You’re completely present, clear, and authentic.

How does the formal practice of meditation benefit the process of making art?

SHW: Because you have meditated, you have this incredibly awake nervous system, and clarity of mind. Those are excellent places to make art from.

JC: We are also able to see our emotional landscape or what’s arising in the mind. So when I think of clarity of mind or presence, I also feel that we’re present with what’s going on with us. So, if we’re feeling sorrow, jealousy, or any particular emotion, we actually can embrace that and express that clearly in what we’re painting or building.

There seems to be a sense of going beyond embarrassment in this approach.

JC: I see embarrassment as sort of an overlay to our authenticity. We are experiencing something, and we overlay it with a “should.” Then, what’s reflected in the painting is the “should” rather than the actual, authentic, direct experience. That’s where the problem comes in because the artist is actually expressing aggression towards themselves and that aggression translates into the artwork and then into the viewer.

How does one avoid that?

JC: Well, it’s something that very important to notice. It’s not so much that it won’t happen, but I think one can discriminate in the process and actually develop an appreciation for recognizing when one enters shame or embarrassment and sees that as path rather than making it into a problem. I hope that’s not too complicated. (laughs)

Jane Carpenter

Would you say that the activity of making art is itself a meditation practice?

Sue Hammond West

SHW: Well, making art could be meditation in action. You could actually go at it for all the wrong reasons–for all the self-loathing and neurotic tendencies–and actually come out on the other side with clarity. It could take a while, depending on the depth of the feelings that you’re working through, but there’s always that possibility.

So, it can be beneficial like sitting…

JC: Absolutely, it can. For some people, sitting is not going to be their choice to experience their life fully. Art is a method, we could say, for bringing oneself into the present moment. It can be contemplative practice, or, as Sue was saying, meditation in action.

So, making art and meditating can have similar results. I have the feeling, though, that striving for that result may not be the point.

SHW: Well, the nice thing about meditation, and art as well, is that you can do it for no result. When you surrender to the fact that there’s no right or wrong answer, and simply allow whatever is happening to happen, that’s when something shifts in your being.

What would you say are some of the most common obstacles to the artistic process being a meditation in action?

JC: One thing that comes to mind is self-consciousness, or a goal-orientated approach. If there is any expectation–of perfection, or getting a particular concept across to the audience, or any outcome at all–then one is a bit ahead of themselves.

SMC: Can you describe an alternative approach?

JC: We can be willing to look at something that looks really strange and be curious about it as opposed to labeling it “bad,” or “not as good as the other person’s.” So I think with a true artist, with this approach, we’re going beyond a dualistic, “good” and “bad,” view.

So, are all works of art equal?

JC: It isn’t some kind of naive “everything is great” attitude. Some pieces will work, and some won’t. But the process is much more alive.

Finally, how will the practices utilized in this retreat work with the obstacle of self-consciousness and goal oriented-view?

SHW: We’ll be doing some sitting practice. We’ll be exploring the five wisdom energies, or emotions, in terms of embracing life. And so, I would say that we’re going to be covering the different types of thinking processes and we’ll be talking about the dualistic tendency of those and giving some experiential training on how to become non-attached to those–how to create the clarity of mind that we’re talking about that is the quality that we want to come at making our art from.

JC: We’ll explore questions like: What if emotions do arise when we’re doing art and we don’t reject them? Could we actually feel joy or delight in expressing ourselves fully? So, I think that we’ll be inviting people to play, actually. There will be different disciplines, and when you put it all together, it allows people to be fearless because there is no judgment in the environment. So there is no need to be self-consciousness.

Seems like nourishing situation.

JC: When we work like this we actually find that people retrieve parts of themselves that they haven’t experienced for a long time. Things can actually fall away–that judgment, or even judging the judger. So, we hope that there is a sense of inviting people to really enjoy themselves.

Discipline and enjoyment seem like sort of an odd couple.

JC: There’s an expression that Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche used, which is “discipline and delight.” So often when we talk about discipline we think about burden and sacrifice and this heaviness. I think in the workshop we’re going to be doing, the discipline of meditation and art brings delight. That’s why we do it!

SHW: Ultimately, it’s creating an environment for people to arise completely from where they are and just to notice who they are in the moment.

Sue Hammond West is a painter and mixed media artist who explores consciousness, quantum physics and the phenomenology of being. Her exhibitions include Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art; Beacon Street Gallery, Chicago; and the University of Notre Dame Isis Gallery. She is director of the School of the Arts at Naropa University.

Jane Carpenter began the study of Tibetan Buddhism and Maitri Space Awareness with Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche in 1975. She has taught the practice as an Associate Professor at Naropa University and internationally for over 25 years. Jane leads workshops on Dharma Art, Ikebana, and Contemplative Psychology.

Jane Carpenter and Sue Hammond West will lead Creative Wisdom: Maitri and Art, November 15-17. To learn more, Click Here