by Christopher Seelie

The snowfall began the night before, and by the time we arrived in a loose caravan of 4 cars Zenko-Iba was covered in white. Of the thirteen of us Shambhala Mountain Center staff who came to Boulder on this day to receive instruction in Kyudo—literally “the way of the bow”, a Japanese practice of meditation in action—only one had taken First Shot before. So we did not receive instruction in the snow. Instead we gathered in the free-standing garage, now converted to a shrine room and indoor practice space. The walls were decorated with photographs from Kanjuro Shibata Sensei’s life of practice, along with documents of merit and souvenirs. Three hay bales wrapped in plastic canvas were peppered with puncture holes. The distance was negligible but kyudo is not a sport like the western form of archery, where the distance between archer and target is a concern second only to where on the target one’s arrow enters.

We sat on gomdens and waited as Shibata Sensei—a green 91 years young and recently recovered from a bout of pneumonia—was escorted in with his wife and translator, Carolyn, and their little gray dog. He was dressed in dark wash jeans, a puffy winter jacket, pale grey slippers that had been warmed by the cast iron stove in the corner, and a black winter hat that had XX embroidered in white on the forehead—signifying his lineage identity as the 20th Kanjuro Shibata. We stood, and for a moment of solid silence Shibata Sensei stared at us, taking in our faces with direct purpose before bowing to us and we to him. Then he walked forward and looked closer before bowing again. Once seated, we waited for him to speak but he took his time in communicating. When he did, his command was to relax.

We sat on gomdens and waited as Shibata Sensei—a green 91 years young and recently recovered from a bout of pneumonia—was escorted in with his wife and translator, Carolyn, and their little gray dog. He was dressed in dark wash jeans, a puffy winter jacket, pale grey slippers that had been warmed by the cast iron stove in the corner, and a black winter hat that had XX embroidered in white on the forehead—signifying his lineage identity as the 20th Kanjuro Shibata. We stood, and for a moment of solid silence Shibata Sensei stared at us, taking in our faces with direct purpose before bowing to us and we to him. Then he walked forward and looked closer before bowing again. Once seated, we waited for him to speak but he took his time in communicating. When he did, his command was to relax.

Carolyn explained that he thought we were sitting like elite monks.

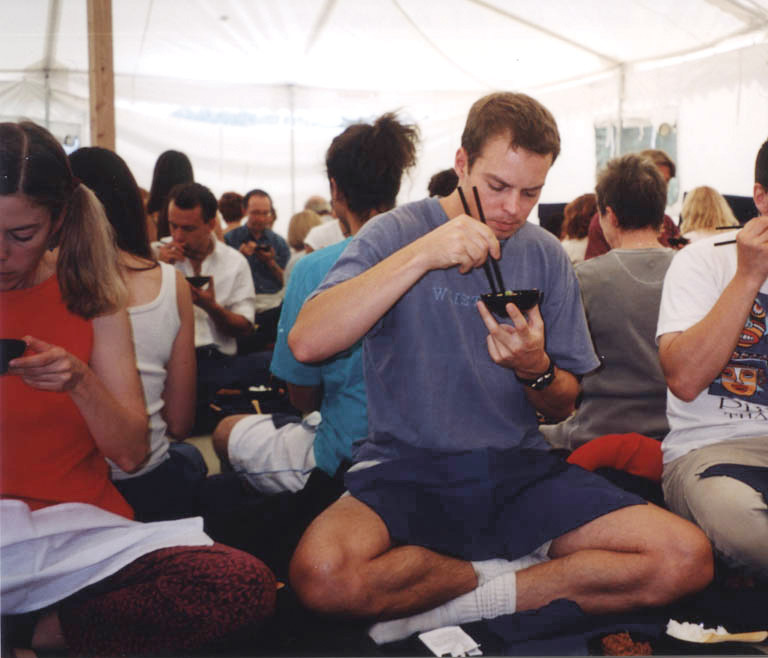

Despite being twentieth in an unbroken line of imperial bowmakers and kyudo masters, Shibata Sensei does not abide dignities and honorarities that build ego. Cutting through the pretensions that could make a ragtag, baker’s dozen of curious students presume to a discipline more severe than warranted, Shibata Sensei told us to relax and then commented on how auspicious it was that the snow was falling. Casually, he told us that from the snow he felt Trungpa Rinpoche’s presence here this morning. He spoke briefly on kyudo as a practice and then allowed for his more experienced students, Vajra, Sue, and Suzanne who had come from Berlin to visit Sensei, to lead us through the stages of the practice.

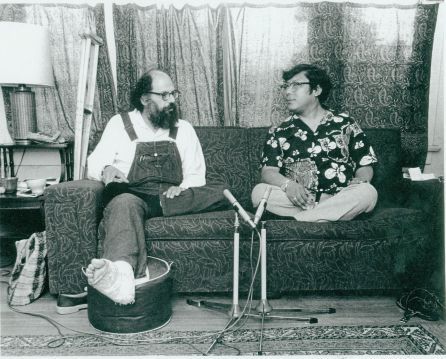

Kyudo is, as Shibata Sensei explained to us, a heart-cleansing practice. The emphasis is on the form one takes in the manner of shooting and the qualities of mind that are experienced in the process. When I asked Shibata Sensei later in the day about the obstacles a practitioner encounters in kyudo, he said that hitting the target is good and not hitting the target is good. “This Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche understood immediately.” When asked how he met Trungpa Rinpoche, Shibata Sensei says it was “very straight kyudo”.

We did not shoot our first arrows that day. The repetition of the form is our practice until such time that we are ready for taking the first shot. From that point, all of Shibata Sensei’s students are of a kind. There are no black belts, no officers, no gold medal winners or blue ribbon archers. These are the honorarities that repel Shibata Sensei’s understanding of kyudo. Becoming familiar with something inexpressible cannot fit into stages of a hierarchy.

“FU RIN KA ZAN” by Shibata Sensei. “Wind Tree Fire Mountain”

The friendship between the founder of Shambhala Mountain Center and Shibata Sensei is a profound example of how different cultures and disciplines find commonality in the wisdom that they share. Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche was a meditation master, an academic and administrator displaced when Tibet was conquered by the Chinese. In his homeland, Shibata Sensei is a living national treasure and a lineage holder patronized by the Emperor of Japan. But Trungpa Rinpoche recognized the power and purpose of Shibata Sensei’s kyudo—a practice developed out of the samurai’s need for heart-training to balance out the fight-training so as to remove pride and aggression with the same tools that might engender it. And while the external differences between tonglen, shamatha, maitri, and other techniques Trungpa Rinpoche brought to the west and the kyudo of Shibata Sensei makes them truly diverse practices, the two men saw through those differences with complete clarity.

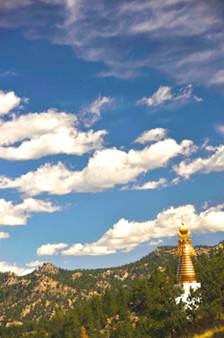

The day ended with tea and cookies as Shibata Sensei answered questions. Last fall, he had made the two hour journey up to Shambhala Mountain Center to give a talk on the importance of making offerings. Since then, the staff has made it a point to offer rice, water, and salt at the Kami shrine that sits behind the Great Stupa of Dharmakaya, nestled in the hills above the MPE campgrounds. Now kyudo too has returned as a regular part of life at Shambhala Mountain Center. May it be of benefit.

Kanjuro Shibata Sensei XX will meet with his students for a kyudo retreat at Shambhala Mountain Center June 30 – July 7th.

I offer a women’s retreat twice a year, on the hottest, longest days in the middle of summer, and the coldest, dark winter days. I see myself as more of a facilitator of this retreat, rather than a teacher. We arrive alone and together, 12 or 15 of us, and we simply practice yoga, sitting, sharing. Something subtle and close transforms because of this turning our discursive gaze inward. There is a luxurious break in the afternoons to hike, read, rest, or visit with each other. Transformation is not always a smooth ride. We have our practices, the support of the schedule, teachings, to hold us—and each other.

I offer a women’s retreat twice a year, on the hottest, longest days in the middle of summer, and the coldest, dark winter days. I see myself as more of a facilitator of this retreat, rather than a teacher. We arrive alone and together, 12 or 15 of us, and we simply practice yoga, sitting, sharing. Something subtle and close transforms because of this turning our discursive gaze inward. There is a luxurious break in the afternoons to hike, read, rest, or visit with each other. Transformation is not always a smooth ride. We have our practices, the support of the schedule, teachings, to hold us—and each other.